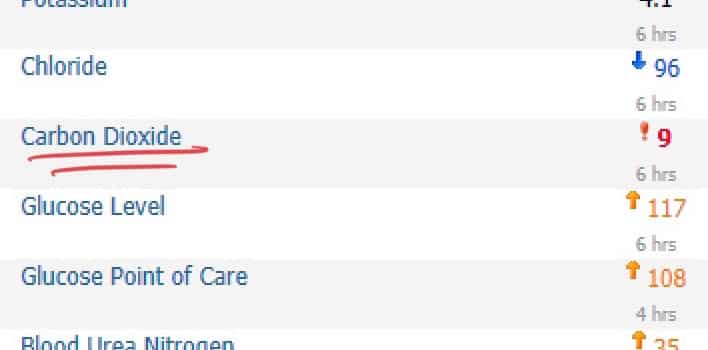

When you obtain a basic metabolic panel (BMP) or complete metabolic panel (CMP), you get the usual values reported on it: Na, K, Cl, carbon dioxide (CO2), glucose, BUN, creatinine, etc. The value that seems to cause the most confusion is the “carbon dioxide/CO2”. This especially happens while I’m teaching on rounds where my mind and tongue switch the “carbon dioxide” to “serum bicarbonate,” “bicarb levels,” or just “bicarb.” It perplexes folks with lesser experience who are usually too shy to ask why I have done this.

Ultimately, acid/base derangements are paramount in the critically ill. We obsess about the details in the ICU. It’s essential to get it right and understand what we are looking at. Time to understand the CO2 on the BMP and bicarb (that’s short for bicarbonate, of course) on the ABG (arterial blood gas)/VBG (venous blood gas). Also, if you prefer to listen to this explanation rather than read it, check out my podcast episode in the links below. It’s available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and many others.

What are we looking for in assessing serum carbon dioxide (CO2)/serum bicarbonate?

Looking at the carbon dioxide level (aka serum bicarb) is extremely helpful in identifying what is wrong with your patient. Things get missed since many must pay more attention to this lab value. It’s my favorite part of the metabolic panel. It’s where the sexy stuff lives. Going over a long differential is different from the point of this post. A downtrending serum bicarbonate/carbon dioxide level should be addressed.

You have NO IDEA how often Intensivists such as myself receive consults for tachypnea with an extensive workup, including chest CTs to rule out PE or look for other funky stuff, x-rays, V/Q scans, etc. All the clinician needed to do was identify that they were developing a metabolic acidosis (the CO2 downtrending) and go down that route. Save a bunch of money and morbidity for your patient. Many times, it’s a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis secondary to saline. Don’t worry, I’m not going down that road.

Why is the bicarbonate (bicarb) called carbon dioxide (CO2) on the lab results?

The analyzers in the laboratory measure the total carbon dioxide content (TCO2). They use enzymatic methods. Methods above my lab knowledge pay grade. Since they measure TCO2, these auto-analyzers do not directly measure bicarbonate (HCO3-). Hence it not being “Carbon Dioxide” rather than “Bicarbonate”. I’ll spare you the organic chemistry process of alkalinizing the specimen to convert the CO2 and carbonic acid into HCO3-.

Why do I personally call it serum bicarb instead of serum carbon dioxide (CO2)?

The reason why we use the term bicarb (HCO3-) instead of carbon dioxide (CO2) is because TCO2 is comprised of approximately 95% bicarb (HCO3-). Close enough, right? The total carbon dioxide (TCO2) includes dissolved CO2, carbonate ions, and carbamino compounds. Figure these components make up approximately 5% of the other stuff. In my book, that’s close enough—my opinion.

The cited paper by Bihari et al., published in the Journal of Critical Care, takes a deeper dive into this concept.

Why don’t the labs agree with the clinicians, change the name, and be done with it?

Remember, we’re dealing with something that has a historical precedent. Technically, it is more accurate to be called carbon dioxide rather than bicarbonate. At first, I wanted to push towards changing the name, but after better educating myself, I am okay with the current structure.

What is the normal bicarb level?

Rule of thumb: 24 mEq/L. The ranges depend on the lab. My shop, for example, uses 22-32 mEq/L.

Why do clinicians check a blood gas when the serum bicarb is low?

Usually, it’s to assess the acid/base status directly. In other words, ensure that the lungs are trying to compensate for the metabolic derangement. For example, if a patient has metabolic acidosis, the normal response should be tachypnea. Blow off the CO2. If the patient has a metabolic alkalosis, they should be attempting to retain some CO2. Again, my explanation is quite rudimentary. I am aware of this.

Bicarbonate levels on an arterial or venous blood gas: are they real levels?

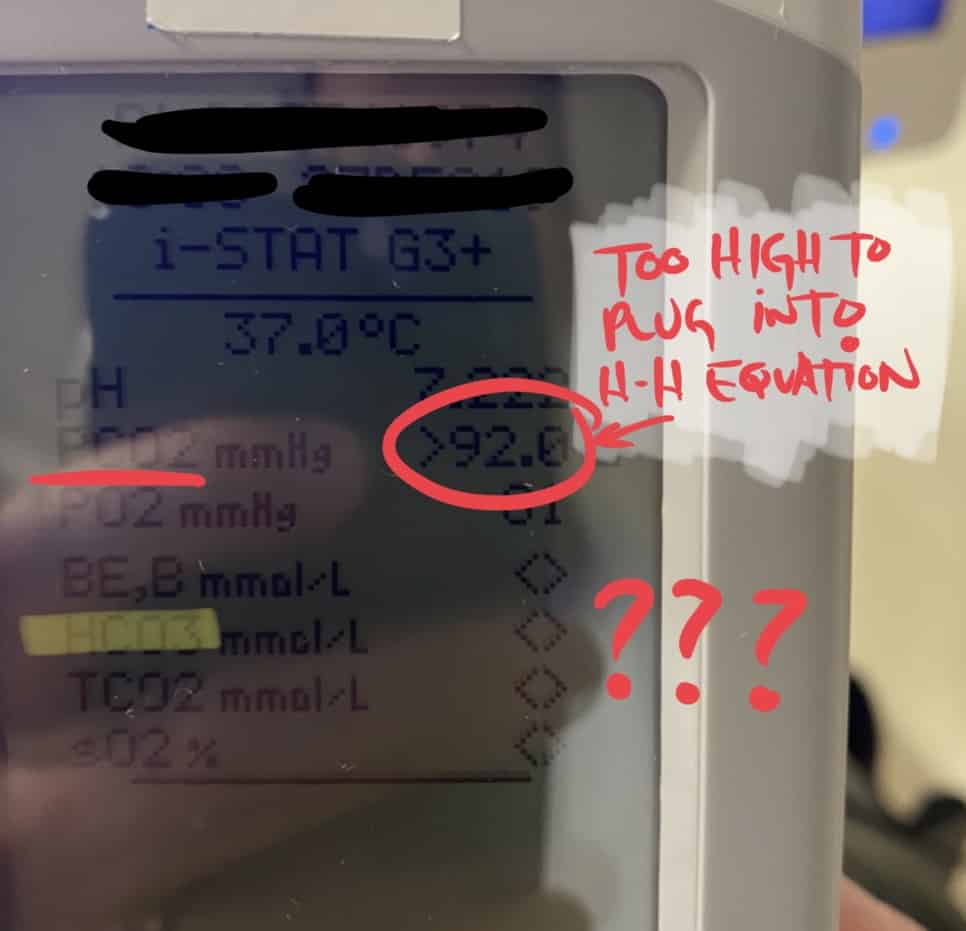

Did you all know this is a calculated value instead of a directly measured one? Do not feel bad because most don’t. This includes many respiratory therapists. When we order a blood gas, the machine measures the pCO2 and the pH. Notice that I did not write HCO3-. The technology used for this is potentiometric methods. Again, I’m referring you to the Bihari et al. paper for more details. Once they have the pCO2 and pH, they can plug it into the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. I know those words make the hair on the back of your neck stand on end. We want to remember only some parts of undergraduate and graduate education. Rishi Kumar, MD, covered the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation in his post HERE.

pH = pKa + log([A-]/[HA])

pH= 6.1 + log([HCO3-]/(0.03x pCO2)

Our blood gas analyzer can detect the pH and pCO2. Using fancy math, it can calculate the bicarb. If the pCO2 is too high, as reflected in the second image, it cannot calculate the bicarb, and you’re left with a blank value.

Are bicarbonate levels from the blood gas accurate and able to be used interchangeably with the lab results?

The short answer is yes. Ultimately, you seek values to help you care for your patient. The exact number being off by 1 or 2 will not change your management. There are some scenarios, however, where the lab can get it wrong and give us low values when the serum bicarb is not actually low. Per Bihari et al., these include hyperlipidemia and paraproteinemia. I can’t say that I’ve seen this in practice. I cannot comment on what values of hyperlipidemia should incite concern. We can see spurious high values in patients with an elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Since the bicarb from the blood gas is calculated via an equation, these spurious results will not be seen.

Case 1: Metabolic Acidosis

This first case was a consultation for a (hypothetical) patient who recently looked unwell and had a high risk of crashing. At the time, they were still hemodynamically stable. The vitals look fine. Clinically, they did not look too bad, just tachypneic. Ultimately, the patient was a ticking time bomb. Throughout the hospitalization, the serum bicarb downtrended from 24, 20, 16, and 15 mEq/L to ultimately this number here. Had this downtrend been more astutely identified earlier, we could have intervened.

If you’d like to read my ultimate lactic acidosis guide, you can click here.

I’m sorry for being short on the past medical history and clinical details. There’s far more nuanced than what I will touch on during this post.

Case 2

Here, the (hypothetical) patient has a metabolic alkalosis. I am not going to go into the extensive differential on this. In the ICU, the majority of the patients who have an elevated serum bicarb are because of metabolic compensation for respiratory acidosis. Examples include chronic CO2 retainers in the case of COPD, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), or obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS). We also see if folks are aggressively diuresing with furosemide and notice a “contraction alkalosis.”

Looking at carbon dioxide/bicarbonate: Wrapping it up

Don’t ignore the serum bicarb/carbon dioxide. Lots of goodies live in there. Also, if you would like to learn why you should think twice before giving your patients with respiratory acidosis bicarbonate, CLICK HERE.

Check out this mini-lecture on my podcast!

Citations for Carbon Dioxide/Bicarbonate

Flear, C. T. G. (1984). Bicarbonate or CO2? Archives of Internal Medicine, 144(11), 2285.doi:10.1001/archinte.1984.04400020219047

Link to Abstract (Full Article is NOT FREE)

Bihari S, Galluccio S, Prakash S. Electrolyte measurement – myths and misunderstandings- Part II. J Crit Care. 2020 Dec;60:341-343. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.06.004. Epub 2020 Jun 25. PMID: 32622663.

Link to Abstract (Full Article is NOT FREE)

Consider purchasing my book, ‘The Vasopressor & Inotrope Handbook’!

I have written “The Vasopressor & Inotrope Handbook: A Practical Guide for Healthcare Professionals,” a must-read for anyone caring for critically ill patients (check out the reviews)! You have several options to get a physical copy. If you’re in the US, you can order A SIGNED & PERSONALIZED COPY for $29.99 or via AMAZON for $32.99 (for orders in or outside the US).

Ebook versions are available via AMAZON KINDLE for $9.99, APPLE BOOKS, and GOOGLE PLAY.

¡Excelentes noticias! Mi libro ha sido traducido al español y está disponible a traves de AMAZON. Las versiones electrónicas están disponibles para su compra for solo $9.99 en AMAZON KINDLE, APPLE BOOKS y GOOGLE PLAY.

When you use these affiliate links, I earn an additional commission at no extra cost to you, which is a great way to support my work.

Disclaimer

Although great care has been taken to ensure that the information in this post is accurate, eddyjoe, LLC shall not be held responsible or in any way liable for the continued accuracy of the information, or for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom.